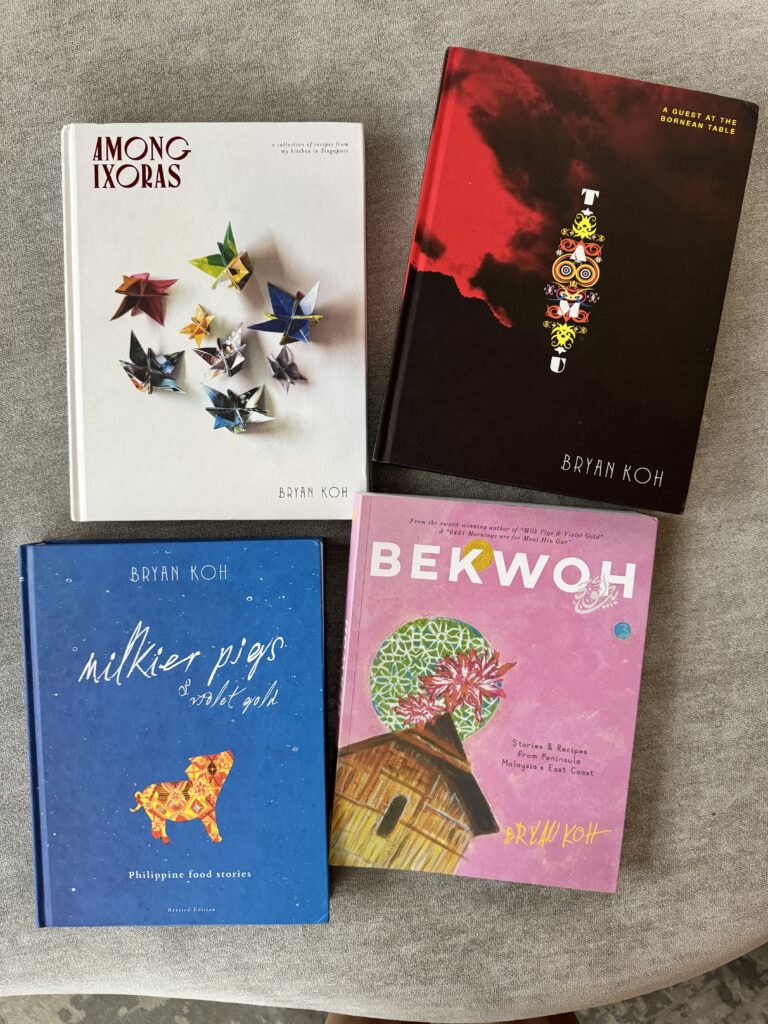

Bryan Koh (@bryankoh__ ) is the author of the award-winning “Milkier Pigs & Violet Gold” (Philippine food stories) as well as “Bekwoh” (about Peninsula Malaysia’s East Coast), “Tamu” (Borneo) and a homage to his childhood in Singapore, “Among Ixoras”. He also founded Chalk Farm, a gorgeous and delicious cake shop in Singapore.

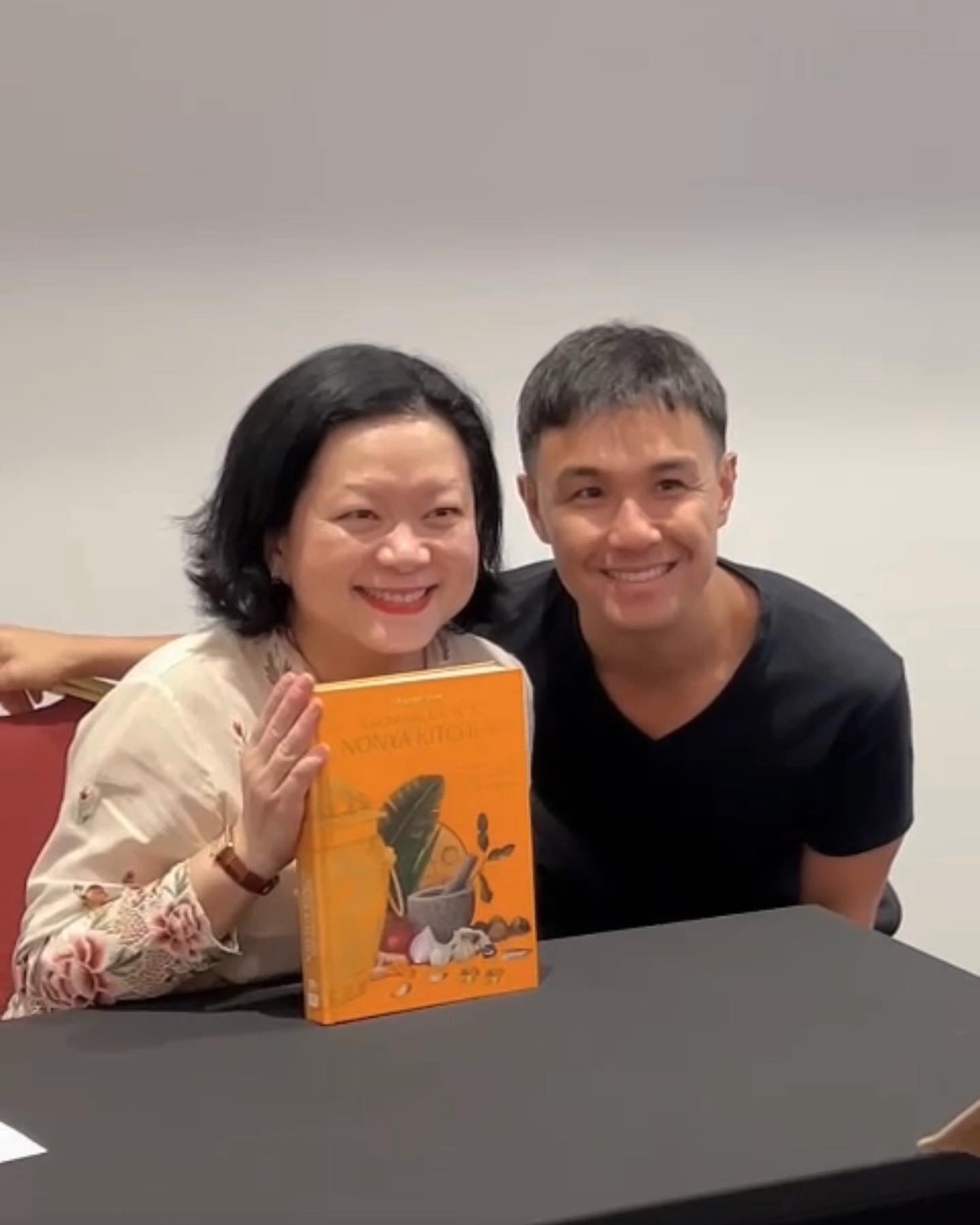

I have only met Bryan Koh once, when he came to my book launch last March. Quite the enigma to me, I am intrigued by him, his output of critically-respected tomes and his luscious cakes on display at his cakeshops. Bryan strikes me as adventurous, sophisticated, entrepreneurial but most of all, disciplined. To be able to churn out book after book set to his design specs, to test and perfect new cake ideas and to go on his culinary/anthropological safaris is no mean feat.

He speaks lyrically, spouting a fountain of poetic adjectives and nouns. It is the same way he writes his books. His work will be treasured for exploring foodways that veer off the well-trod path.

You have a fabulous chain of cake shops in Singapore. Why did you establish one and how did you come about with the name “Chalk Farm”?

Chalk Farm was born out of necessity, in a way. In the interim between my Mathematics degree and my Masters program for hospitality at Cornell, my mother encouraged me to make myself useful – to make some money. So I baked cakes and sold them. I was kitchen-competent and baking involved limited perishables.

I set off to pursue my Masters with no intention of continuing the baking. But after returning, I found myself greeted by numerous cake enquiries. And so the seeds for Chalk Farm were sown. We were solely online for 3 years, opening our first outlet in Paragon in 2013.

Chalk Farm is a tube station along the northern line. When my sister was studying at the London College of Fashion, we used to hang around Camden Town, a stop from Chalk Farm. I was drawn to the name for some inexplicable reason; one of my best friends said it evoked both rusticity and urban sophistication. Perhaps she was right.

How do you come up with the types of cake that you have in “Chalk Farm”?

Chalk Farm is built on Western and local classics with a twist, with a focus on bold, deep flavours and textures. No faff, all pleasure. The repertoire may have expanded, but close to all the originals have remained, from the dark chocolate olive oil to the kueh salat, from the salted caramel macadamia to the lemon yoghurt loaf. For the most part, we have managed to stick to our guns. I am grateful for that.

What advice do you have for anyone who wants to start a cake shop?

A lot has been said about passion, but starting a cake shop – any business, but especially in F&B – requires discipline, patience and stamina. The overlap between what you like and what your customers want is the place to traverse and mine. Also, remember that baked goods that blossom in a domestic setting do not always work in a commercial one.

What got you into writing cookbooks?

Around early adulthood, I began to entertain the idea about writing something food-related for Southeast Asia, quixotic as it sounds. Back then, books on regional Asian cooking were limited. I had been familiar with the works of Claudia Roden and Madhur Jaffrey and found their work inspiring and moving.

I was a freelance journalist for several years, starting midway through university. I was sent by a publication to Lipa, Batangas, Philippines, to cover a detox facility, of all things. After the stint, my domestic helper’s husband, who was in the area at the time, took me out to eat. I was brought up on Philippine food – it was what my yaya would give us for after-school meals. As it had become part of my system, I never thought to explore it. The jaunt around rural Batangas changed that. I spent the next few years travelling, eating, cooking, interviewing, for what would become Milkier Pigs & Violet Gold.

How do you pick what geography to cover?

I select countries or areas, rather, with cuisines that I am curious about myself, which are usually those that have received little coverage. I am fascinated by the (edible) plant kingdom and how people harness the best from what Nature and circumstance have provided. I am also interested in old techniques and flavours, how locals cooked before the advent of modern gadgetry and how they seasoned their foods before they had access to a global larder, so to speak.

Describe one of these exploratory trips?

I remember visiting Tuguegarao in Cagayan Valley Region in the Philippines in 2012. They have something called pancit batil patong, a stir-fried wheat noodle dish served with a soup made by deglazing the calloused wok with broth. The noodles were made on site, in the panciteria, the lye-enhanced dough thumped into sheets by a large beam of wood that the cook would bounce on as if it were one end of a see-saw, razed by a fierce cleaver, steamed and fried with the carabao meat and vegetables over woodfire. The steam, the smoke, the sweat. It was a riveting experience.

I also recall visiting Putao, in the northernmost part of Kachin State, Burma. People usually visit to catch views of the Himalayan foothills. I went to investigate the foods of the Lisu and Rawang. It was fascinating, the vegetables, fish, grains, insects and riverweed that were being consumed, many of which are not known outside the region, let alone the country. I took notes, photographs, videos and soundbites, as per routine, and consulted botanist and animal biologist friends as well as research papers and science journals, in efforts to identify their binomial names.

What was the hardest place to get to? What has been the most memorable experience on any of these trips? Was there a harrowing one?

The hardest place to reach was probably Bario in the Kelabit Highlands. I intended to visit the 2018 food festival and all the flights were full. Due to other unforeseen circumstances, I had to take a jeep from Miri and spent 14 hours negotiating rough terrain on dirt roads.

An hour before reaching Bario, we had to stop because the muddy road had been severely runkled by rain and the crunching wheels of large vehicles, probably transporting timber. It was close to midnight, it was cold out and our chief sources of illumination were our phones and jeep headlights. The driver analyzed the situation, ordered us to get in, and through some skillful manoeuvring, got us through.

What’s the most challenging ingredient you have tried?

I have had a fair few! Right now, it’s probably fermented djenkol beans. A decade or so back, it would have been bile and stomach juices, with which certain ethnic groups in the Philippines, Thailand, Laos and Burma, lace their meat salads and soupy braises, but I have warmed up to them tremendously.

You have a signature style with your photos. What are your guidelines in terms of styling, lighting and props?

I think of it as food portraiture. I like things straightforward, with minimal clutter, caught in the (occasionally jarring) interplay between shadow and light; I always use natural light, even if it is a pain. Bjork once said she was attracted to things that were pretty but brutal. My senses resonate with that.

What are your other hobbies?

Cooking, taking photographs and writing were once hobbies. Now they have become part of my work. I quite enjoy painting, having trained under a virtuoso in Chinese watercolour and calligraphy when I was younger. I also swim. I like being in water.

What kind of music do you like?

I ingest music from all genres, but listen to mostly electronica these days. Goldfrapp, Björk, Röyksopp, iamamiwhoami, Róisín Murphy and Yaeji, I particularly enjoy. I also like Florence + the Machine, Sade and Grace Jones.

If you could plan a feast for loved ones, what would your menu look like?

I know it’s not very fashionable, but I am very keen on carbohydrate.

I’d begin with a small (or not so small) portion of noodle, either a Kelantanese laksam or prawn mee (hae mee) done in the Penang style, that’s to say, devoid of sweetening spice and with the sambal redly cooked into the broth.

I would then have steamed rice, supported by a variety of viands. A Philippine coconutty stew of yellow-fleshed squash and shrimp (guinataang kalabasa). A lip-puckering, annatto-red adobo of beef or pork. A Bamar salad of citron (shauk thee thoke) or ginger (gyin thoke). Fern fiddleheads or bracken fern fried with belacan.

For pudding, leche flan, scented with dayap.

Perhaps little pouches of Statins as door gifts.

What would you like to do ten years from now?

To be still fascinated by the world and engaged with whatever I am doing. It need not be food-related.