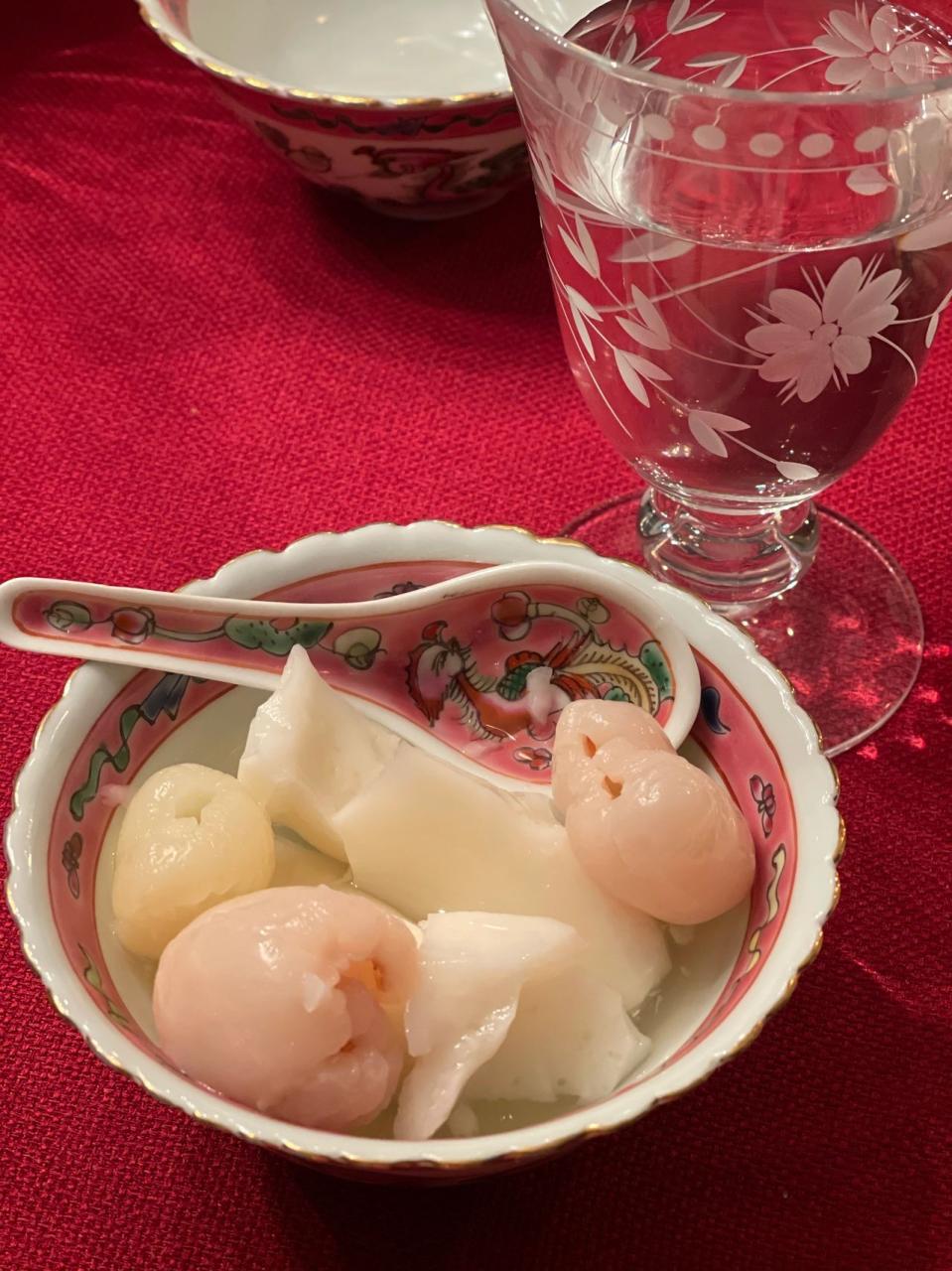

Place setting at The Peranakan Museum

My pet peeve with my Americanized family is when my kids pull out forks to eat their white rice. I get so annoyed. Rice might fall through between the fork tines. A Chinese family typically eats rice out of a bowl with chopsticks. A Peranakan family actually does not. We use a dinner plate along with a fork and spoon, accompanied by a Sheffield knife at times. (The Sheffield knives in my family were used to slice popiah spring rolls.) So what do I use at home? A plate, fork and spoon and knife of course!

As I wrote in my cookbook (page. 53), Peranakans “adopted the Anglo-Indian custom of using forks and spoons, with the exception of Chinese soup spoons to accompany the soup bowls.” That is why you will find lots of Chinese spoons among the beautiful Peranakan dinnerware, but not necessarily chopsticks that are uniquely Peranakan. The stainless steel forks and spoons tended to have traditional rocaille filigree and were often made in England.

In the cookbook (page 219), I said that “we did not always eat elaborate meals.” Our daily meals were a lot simpler and I called my chapter “Our Daily Fare” to reflect on the biblical and practical source of sustenance. “My father was an old-school Baba who believed that daily dinner should consist of a soup, one vegetable, perhaps some pickles and belachan, and two other dishes consisting of meat or fish. These were served family style, with plain white rice as the staple. It was his habit to scoop soup and drizzle it over his plain rice. He was particularly observant about table manners. He forbade us from stacking plates while we ate, saying that it was taboo or else one would owe money to others. He also disliked children eating with their elbows resting on the table. My mother had her superstitions too. One should not settle a bill while still eating or be subject to someone else sweeping at her feet while she was still dining. Early on, we all scooped from a large communal soup bowl. Over time, it seemed only healthier to have our individual soup bowls.” (page 220)

Chinese New Year was a different matter altogether.

As I had written (p.53), “lunch was a Tok Panjang which literally meant ‘long table’. The term itself reflects the intermingling of Malay and Chinese vocabularies since Tok is a Hokkien (Fukienese) word for ‘table’ and Panjang is a Malay word for ‘long’. Peranakan Chinese families often owned an extendible table specifically for the Tok Panjang feast. In fact, it is a habit I have kept. I own one such table and conveniently extend it when I throw dinner parties. On this most important occasion – Chinese New Year – my mother used the formal extendible table to seat several people at a time.

On the table, we laid out a full spread of the soup and gravy dishes, pickles and sides served on our best china. Whereas Western family style entailed one big platter for each dish, we served on smaller plates and placed two or three of the same offering spread across the table. In a typical Tok Panjang, the table continually turned over to serve a meal to family members and visitors. Of course, my father, being the patriarch, ate first. Old family friends and relatives would join us for lunch. There was surely a pecking order as the brothers-in-law and finally the youngest ones took their place after the elders got up from their seats. The dishes were continually replenished. This Tok Panjang would go on throughout the afternoon and by dinnertime, the whole process would repeat once again.”

These were my privileged memories of growing up in a traditional Peranakan family and I continue to embrace these practices today.

Excerpt from “Growing Up in a Nonya Kitchen”, 2012. All rights reserved.

Excerpt from “Growing Up in a Nonya Kitchen”, 2012. All rights reserved.